The section’s opening remarks were delivered by dean of the Department of Political Science and Sociology, Artemy Magun, who spoke about the history of right-wing Russian thought. Conservative ideology was born in Russia as an elite movement in the form of a defensive reaction to the French Revolution. It’s objective was mainly to preserve the status quo, with a strain of rather utopian romanticism in the spirit of “the past was better.”

In the 20th century, however, after the revolution, this casuality disappeared and nationalism remained, shifting from its elite status to a more popular one. If we look at the dissident liberal intelligentsia of the 1970s and 1980s, we see that there was a significant drift to the right. In their own eyes, the intelligentsia was more like Western conservatives at that time than liberals.

Naturally, this process had a strong impact on perestroika. For example, the Communist Party of the Russia Federation (KPRF), created in the early 1990s and formally leftist, takes ultraconservative positions on social issues. The Liberal Democratic Party, which actually corresponded to its own name at first, quickly moved toward right-wing rhetoric.

Next, Maria Kochkina presented a study on the immaterial workers and the new spirit of capitalism. She explained that the new ideology of these workers is to attempt to show their worth in the labor market (as examples she refers to such terms as “my own project,” “start up,” etc.). In reality, competition in this market is rather high, and as a result immaterial workers work for relatively low wages and have an unlimited workday, making them quite a vulnerable population group. However, they perceive themselves as having a high social position, from which stems a certain “chauvinism of prosperity.” When criticizing illegal migration, for example, representatives of this social group do so in terms of economics and the global labor market.

According to Kochkina, contemporary Russian right-wing movements have emerged on the wave of this chauvinism. Two of the most popular movements are “The Movement Against Illegal Migration” and “Sputnik and Pogrom”. The spectrum of ideas of these movements includes and eclectic mix of neoliberal, nationalistic and even imperial ideas. Kochkina gave the example of a movement whose main thesis is based on the necessity of building a nation-state, however its true output would really be an empire.

Next, Anna Kadnikova presented a study on the attempt to ban abortions in contemporary Russia. Abortion legislation in the USSR in the late 1980s was one of the most liberal in the world, and Russia inherited that tradition.

In 2011, however, Elena Mizulina introduced a bill with a set of amendments to article 56 of the federal law “On Protecting the Health of Citizens,” which would seriously restrict abortions. The amendments were not accepted, however, and since then a wide-ranging debate has begun in Russia on the issue. The terminology and even the names of the parties presenting various positions on abortion are fully identified with the west, and the movements for and against banning abortion are the same as in the United States: Pro- Life and Pro-Choice.

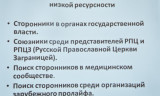

Kadnikova then spoke about Pro-Life in Russia. The basic ideology of pro-lifers is that killing an embryo at any age, starting with the day of conception, is infanticide. In Russia, similar movements have rather strong religious and anti-western overtones due to their cooperation with the Russian Orthodox Church and the government. From the beginning, the method of public influence for these movements has been trying to bring over women who are unsure of whether or not to have an abortion, being at the stage of the so-called “crisis of pregnancy.” Moreover, in recent years these conversations have been increasingly conducted in religious terms.

After the conservative turn in Russia, these movements changed and their discussion shifted to a legislative ban on abortions and influence on wide public—which, according to interviews collected by Kadnikova, members of the movement had not even thought about prior to the conservative turn.

The section was concluded with an interesting discussion neither in criticism or praise of the presenters, but rather on Russian nationalism and an expansion of the topic.

Gennady Yakovlev