Konstantin Severinov, professor at the Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology and head of the Molecular, Environmental and Applied Microbiology Laboratory at St. Petersburg State Polytechnic University, gave a lecture in the Conference Hall.

What might explain the similarity between all living things? We agree that this similarity is due to common ancestry, though there are parts of this hypothesis that are not necessarily true.

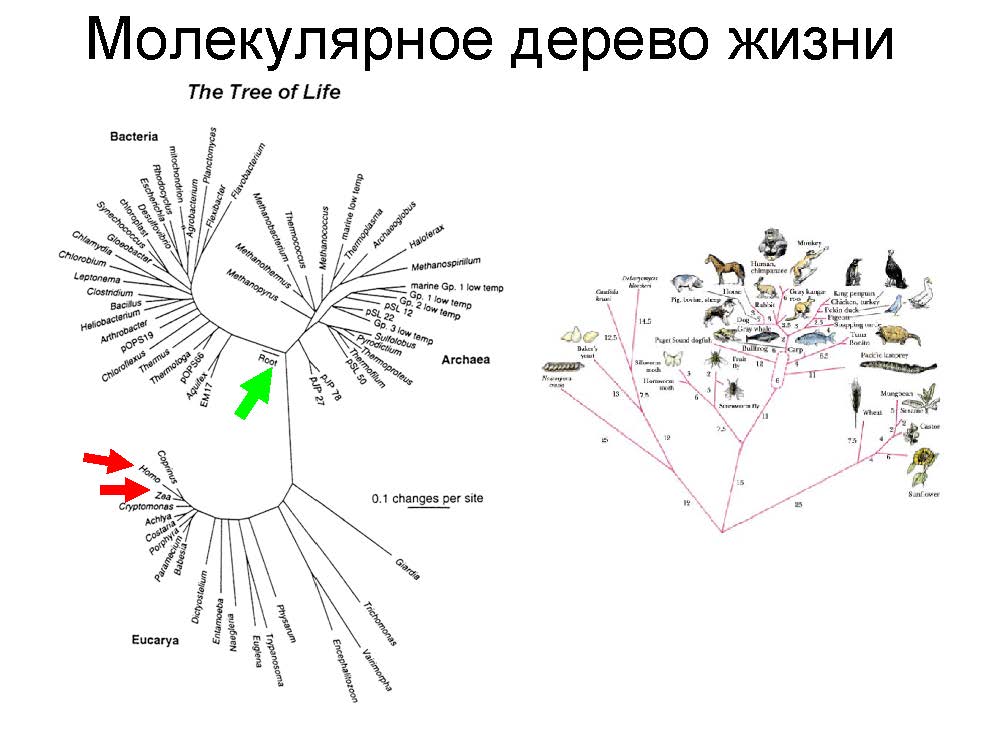

There is a well-known tree of life from the Victorian era, on which a white human male is drawn on top. This tree was constructed on morphological comparison and shows, specifically, that evolution had a goal: the white male is at the very top, above the other ancient and abnormal beings.

How can we identify when other forms of life emerged? Through examining the fossil record. Geological strata can be dated very accurately thanks to radioactive analysis. Certain types of remains are found in different layers: reptiles are lower than mammals, and amphibians are lower still. With such an approach we can construct the very same tree. But the fossil record offers no information on invertebrate creatures.

There is another method for examining life: considering the sequence of DNA letters from part of the human genome or that of any other living creatures. We can examine life without relying on morphological features, but rather upon these genetic texts. This is a purely linguistic exercise in which we compare texts and observe the results. The human genome, which was determined 10 years ago, in the linear sequence of three billion letters. In contrast to the Russian language, which contains 33 letters, DNA contains only four. Still, the text is very long indeed.

How can we determine the degree of genetic kinship between two organisms, or two humans? By reading these texts, we can simply compare them. The degree of difference between any two humans is 0.1%, or one letter out of thousands. This means that each of us is different by three million letters, or typos. We differ from chimpanzees by 1%, but we are still very similar.

We can now perform something called molecular phylogeny. The nucleic acids from different organisms have similar sequences; by counting the number of differences, we can construct a tree. At first, this tree looks very similar to earlier models depicting the origins of life, but it is not oriented as a striving toward man. Plants, for example, are a little further away from us on this tree than all other living beings.

While scientists were preparing to read the three billion letter human genome, they had already read several thousand bacterial genomes. Bacterial genomes are much shorter than ours, and in considering bacteria, we can build a huge, universal tree of life.

On this tree there is a group of eukaryotes (organisms whose cells contain a nucleus) and two groups of cells without nuclei — bacteria and archaea. The absolutely enormous diversity of life is concentrated in bacteria, archaea and single-celled organisms that we cannot even see. What is visible to the naked eye is only a very small fraction of the diversity of existing life forms. There are no viruses on this tree, as it represents only cellular life forms. Viruses are even more diverse than living organisms. Every life form has its own viruses. But their diversity is not directly related to the diversity of this cellular life.

This common tree has a root to which we arrive from any existing form of life with a minimum number of changes based on an analysis of a given genetic text. It is a being that no longer exists, but has been given the biblical name of LUCA (last universal common ancestor). At the time that LUCA lived, it was very complex. It already existed as our contemporary understanding of a cell. What preceded it is still unknown.

How do we determine when LUCA lived? The rate of the development of life is bound up in the geological record. Next, we make a hypothesis, such as that of molecular time, which refers to the number of changes in the genetic sequence over time. Having made this hypothesis, we can extrapolate to the root. It turns out that this creature lived somewhere around three and a half billion years ago.

Where did LUCA live, and what were the physical and chemical conditions of its existence? If we restore the genetic text encoding a protein specific to LUCA, we find that it functions in the best way at 70-80 degrees centigrade. This suggests that the organism from which this protein is reduced also existed at the same temperature. This correlates well with the fact that three and a half billion years ago, the Earth was hot.

If we perform phylogeny of one gene, of one “word,” we come to one point. We interpret this as one organism that is the origin of this gene through a direct relationship. If we construct the same tree for another gene a common ancestor will arise there as well, and it, too, can be quite ancient. LUCA was certainly not alone.

What this describes is called “vertical evolution,” in which genes are passed onto offspring and are somehow changed in this process. There are also cases of horizontal transfer. Whenever such an event occurs in biology, vertical evolution is disturbed because something has violated the rules, and the horizontal skips over to another place, to another organism. This process was important for the emergence of beings such as ourselves. Viruses were evidently agents of such transfers. They are genetic vectors that simply carry over one gene to a different place.

The schematic for the emergence of life is now available. Everything was hotter, LUCA existed somewhere, and then came our cells, archaea, and bacteria, though significant transfers did occur. In particular, what became an ancestor of all of our cells (the cells of higher organisms) were ancient bacteria that became trapped at some point, and became mitochondria.

Genetic information is transferred to offspring from one generation to another. The process of sexual reproduction, from which we all emerged, works as follows. We actually contain two sets of genes of 1.5 billion letters each — one from our mother and one from our father. Those chromosomes and genes that we have in pairs are separated and emerge as single sets, which, in fact, are then transmitted in the form of reproductive cells that are eventually reconnected and emerge as an organism with a double set.

We have 46 chromosomes: 23 come from our father, and 23 from our mother. The mother has 46 chromosomes, 44 of which are utilized. The remaining two are simply XX (and in the father, XY). When the mother and father produce an offspring, the chromosomes are combined to produce either a girl or a boy with the same frequency. Y-chromosomes are transferred exclusively through male lineage.

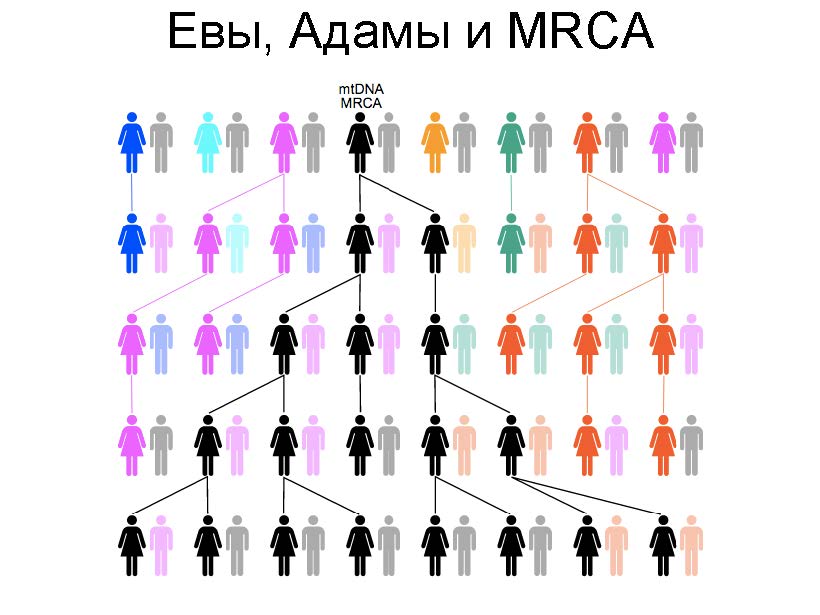

If we trace the transmission of Y-chromosomes through generations of ancestors, we arrive at one man who is in fact the Y-chromosomal Adam, and the direct source of the Y-chromosome of all existing males. We can more or less assess how frequently human beings propagate themselves. These mathematical models suggest that the Y-chromosomal Adam existed rather recently, about 50,000 years ago. He was, evidently, human.

We can do the same with women. The egg cell is very large and contains mitochondria in addition to its own chromosomes, which are inherited by both boys and girls only through the maternal line. We can perform the same trick with mitochondrial DNA as with the Y-chromosome and arrive at the same source — a single woman —who transmitted mitochondria to all currently living men and women along the maternal line. It is believed that this mitochondrial Eve existed about 150 thousand years ago.

Virtually every gene has its own Adam and Eve (just as there are a plurality of LUCA for different genes). Eve is the source of all mitochondria in the maternal line, but she was not alone. It’s not as if other women didn’t exist along with her, it’s just that they didn’t transmit their mitochondrial DNA to all extant modern people. For every group of sequences, it’s possible to construct their own Eves and Adams. During evolution genes are transferred, along with their combinations. Organisms, as such, are not responsible for this. They are simply the mechanism by which genes are passed on and on.

Maria Momzikova