The second day of a conference organized by the French Consulate and the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration (RANEPA) took place at the European University.

Attendees were exposed to the historical framework of migration processes in Russia and in France, and the countries’ experiences were compared. Conference speakers included government officials (Igor Bartsits, Alexnder Marchenko, and others) and leading researchers in the field of migration (Vladimir Mukomel, Philippe Fargues, and others). Important issues concerning the politics of adaptation and integration were raised in a variety of reports and round table discussions, and are outlined below.

In his report, Philippe Fargues (European University Institute, Florence) posed the question of whether migration could help Europe emerge from its current state of crisis. According to Fargues, the peak for migration is around 25 years of age, a fact that is illustrated by the historical experience of various countries. At 25, a person’s productivity is at a maximum (the greatest number of Nobel Prizes have been awarded around age 33). In this light, labor migration allows labor productivity to grow and, additionally, highly skilled migrants enable technological progress. Europe needs to attract talent, and this, according to Fargues, will help it emerge from the crisis. Another issue that Fargues addressed was whether or not low-skilled migrants constitute a burden. He came to the conclusion that niche economies exist, and are filled by low-skilled migrants. He gave the example of the process of producing Parmesan cheese in Italy, which is one in which migrants participate directly (the majority of herders in Italy are Indian citizens). Fargues then brought up the issue of circular migration—those migrants who have no motivation to obtain citizenship. This is bad in his opinion, and such migration is undesirable.

Vladimir Mukomel also delivered a standout presentation. In his report, Mukomel examined the dominant discourse on migration, how agents in the labor market view themselves and their foreign colleagues, and, accordingly, how foreign workers view their “local” colleagues, their relationship to their employer, their wages, and their social guarantees. Mukomel set himself the task of determining whether competition exists between migrants and “natives”. On the basis of a statistical study, he concluded that competition is more likely to occur between legal and illegal immigrants, who, according to him, receive more. He also compared external and internal labor migration, saying that migrants are equally highly motivated, and thus work harder and receive more than the “native” population. The only difference is that Russian workers are better educated and more qualified, so the wages of internal immigrants exceed those of external immigrants (“The effect of motivation is superimposed on knowledge” said Mukomel, best illustrated by the example of migrants in Moscow).

Another interesting presentation was given by Igor Bartsits, director of the International Academy for Public Service and the Administration at RANEPA. His primary thesis consisted of the following: in accordance with a critical decrease in the number of graduates of Russian schools and universities, it is necessary to re-orient for a global market and attract foreign students in order not to reduce staff or to lose qualified instructors. Bartsits also emphasized the fact that higher education in Russia is still considered “good;” however, it remains unattractive because of the rigid systems of control over students. He did not provide any solutions to this complex situation.

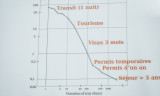

Of particular interest was the discussion that took place in the course of a round table on projects regarding the social integration of migrants. These projects are briefly outlined as follows: Leandro Montello spoke about the Bureau for Migrant Integration in France, and the example of Dijon. The Bureau draws up an agreement with first-time migrants to France that provides training in three areas: eliminating gaps in their knowledge about life in France, on cultural norms and rules, and everyday life. Migrants also receive training in the French language and information about employment. This, according to Montello, is the most important part of the training program. Montello did stress the fact that not everyone has the opportunity to commute to a regional center to fulfill language courses. As a result many immigrants remain un-integrated. In addition, Montello described possible durations of stay for foreign nationals in France, and said that issuing an annual registration is ineffective. Financially speaking, a longer-term registration would be much more so. Such a possibility exists, but is rarely granted. Another issue brought up by the program is what to do once an immigrant has passed their language courses. In Montello’s conclusion, it is evident that integration initiatives must be expanded.

Remi Gallou highlighted the problems of immigrants who arrived in France in the 1960s after leaving African countries and the Maghreb. These are former labor migrants who have now reached the age of retirement. They are generally single, as their families remained in their country of origin. In addition, their living conditions have been subpar throughout their lives—the French government granted these migrants dormitories in which they have lived until now. These dormitories now need repair or resettlement — a problem that must be addressed at the state level. Gallou emphasized the need to draw the public’s attention to the issue, saying, “We must acknowledge their presence and working years in France, and must acknowledge their dignity.”

Maksim Parshin spoke about the Orthodox Church’s work with immigrants in Russia, and, in particular, with migrants from Central Asia. Training courses began as part of joint initiative between the Russian Orthodox Church and the Federal Migration Service. The program includes training in Russian language and culture, as well as a unit on the study of migration legislation. Such training centers are already open in Khabarovsk and Kaliningrad, as well as in Tambov and Orenburg oblasts. “We’re trying to help migrants in their integration — to help and protect,” said Parshin. This includes protection from the influence of diasporic organizations, which, in Parshin’s view, interfere with cultural integration. “We say that in any country to which a migrant arrives, he should become integrated, and know and respect the customs and traditions that exist in a given territory. We offer support and seek to instill knowledge so that there are no conflicts with the local population. In France in 2005, migrants caused riots; in Russia certain moods arose within the native population in relation to the number of migrants who did not want to integrate,” said Parshin. Concluding his report, Parshin emphasized the need to establish such training courses in the workplace and in the community.

Akhmad Makarov spoke about the activities of the Department for Working with Migrants of the Administration of Muslims of the European Part of Russia. The Muslims of Russian regions — ethnic Tatars — come from Central Asian common madhhabs, or schools of Sharia law. In addition, Tatars and Uzbeks have related languages, and the historical ties of Russian and\ Central Asian Muslims are “much older” than we have thought. These commonalities can be used so that the immigrants cease to feel like strangers in the host community, said Makarov. In his view, the revival of Muslim traditions can help manage the societal problems caused by the migrants in Russia. But betting on language-learning alone is not entirely justified, according to Makarov. In response to this view, the Administration has launched a project to translate Tatar and Russian literature into Uzbek and Tajik languages.

The most important issue that the speakers were asked to respond to was how they see an integrated immigrant. The speakers’ opinions could be divided into two groups: some believed that such a migrant would be familiar with Russian culture and would not violate Russian laws. The other group believed that the integrated migrant is one who considers him or herself to be integrated. “In one way or another, all answers relate to the migrant’s individual attitudes,” summed up the respondent “the problem is that an adult person must change attitudes; integration occurs in a quasi-culture, and migrants are integrated into a parallel society.”

Overall, the conference led to a fruitful discussion and once again set forth the issue of differences in paradigms for considering immigration in the academic and non-academic community. These differences led to an interesting discussion, and the opinions of the French participants helped see migration through the prism of French experience.

Aleksandra Alekseeva